2022 in books

/I read a lot of good books in 2022, and I had a hard time narrowing them down in the “best of” categories I typically use for these posts, and once I had done that I still had a lot to say about them. So let me end these introductory remarks here and get you straight into the best fiction, non-fiction, kids’ books, and rereads of my year.

Favorite fiction of the year

This was a fiction-heavy year of reading thanks in no small part to two wonderful series recommended by friends, about which more below. I present the overall favorites in no particular order:

Wait for a Corpse, by Max Murray—A really charming and witty mystery from the early 1950s in which the mystery is not who killed the narrator’s awful Uncle Titus but who is going to. A genuinely romantic will-they-won’t-they love story, a variety of humorous and farcical plot complications, and a dash of small-town political shenanigans round out this fun story. Long out of print and probably hard to find, but worth seeking out.

John Macnab and Sick Heart River, by John Buchan—This year I declared my birth month John Buchan June and read and wrote about as many of his novels as I could. I squeezed eight in, and these two were my favorite new reads. One a high-spirited outdoor heist caper set in the Scottish highlands, the other a moody and contemplative outdoor odyssey through the furthest reaches of the Canadian Rockies, both are excellent, gripping, absorbing reads, albeit in dramatically different ways. You can read my full John Buchan June reviews of John Macnab and Sick Heart River here and here.

Fatherland, by Robert Harris—A Kripo detective in Berlin investigates the murder of an obscure Nazi Party functionary as the city prepares to celebrate Hitler’s 75th birthday—in 1964. I’m not usually one for alternate history, but Fatherland approaches a fantasy world in which the Nazis won World War II through a brilliantly structured mystery-thriller, giving the reader two levels of investigation and discovery that interlock with and complement each other. It’s vividly imagined, plausibly detailed, and briskly written. “I couldn’t put it down” is a hoary cliché, but in this case, for me, it was true.

And the Whole Mountain Burned, by Ray McPadden—A strongly written and hard-hitting novel about two soldiers—one experienced, one green—in the United States’ war in Afghanistan.

Butcher’s Crossing, by John Williams—The story of a buffalo hunt in a remote pass of the Rockies, Butcher’s Crossing balances a gritty, sweaty, bloody plot with intense character drama, pitting the naïve and sentimental New England boy Will Andrews against the Captain Ahab-like Miller, the guide and trigger-man leading the expedition. Beautifully written and gripping. I blogged about Williams’s use of the senses in Butcher’s Crossing here.

The Daughter of Time, by Josephine Tey—A severely injured police inspector tries to solve a 450-year old mystery from his hospital bed. It’s better than it sounds—astonishingly good, in fact. Full review from last month here.

And Then There Were None, by Agatha Christie—The work of Agatha Christie is a weird lacuna in my reading, and until this year the only one of her novels I’d ever read was Murder on the Orient Express way back in high school. I fixed that this fall with one of her other most famous books, And Then There Were None. This review will be short: it’s regarded as a masterpiece for a reason.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, by Edgar Allan Poe—Poe’s only novel, Arthur Gordon Pym purports to be the journal/memoirs of a New England youth who stowed away on a ship and got considerably more than he bargained for, including mutiny, shipwreck, cannibalism, ghost ships, and a final voyage into terra incognita, violent encounters with undiscovered peoples, and… something far worse. Poe combines Moby-Dick-style kitchen sink realism, a Robinson Crusoe-style spirit of adventure, and plenty of his own trademark feel for the uncanny and terrifying for an engaging and uniquely thrilling tale. I had only ever heard bad or dismissive comments about Pym up until this time and was very pleasantly surprised by it.

The Passenger, by Cormac McCarthy—Cormac McCarthy’s first novel since The Road sixteen years ago starts as a sort of New Orleans No Country for Old Men in which Bobby Western, the brilliant son of a Manhattan Project physicist who is now a salvage diver, starts his own investigation into the mysterious crash of a private jet in the Mississippi River only for terrible unseen forces to array themselves against him. This storyline is interspersed with that of Bobby’s sister, a child prodigy afflicted with intrusive schizophrenic hallucinations, whom we know from the opening pages eventually hangs herself. But neither storyline goes anywhere, exactly. Long, talky, meandering (none of which are intended as criticisms), The Passenger is as vividly written as any of McCarthy’s other work but clearly has much more going on in it thematically than the straightforward plot elements, and I knew even while reading it that it would stick with me and reward me more later through simply letting it sit in the back of my mind for a while, and that has proven to be the case. But that doesn’t make it a completely satisfying read. So, caveat lector. The companion volume focusing primarily on Bobby’s sister and her institutionalization, Stella Maris, is already out but I haven’t gotten to it yet. We’ll see how this informs and recasts the events of The Passenger in the new year.

Witch Wood, by John Buchan—I read this just a week or so ago, so you can expect a full, thorough treatment this coming John Buchan June, but for the time being let me recommend it as a strongly written, engaging, atmospheric, suspenseful, and genuinely spooky historical novel in which a young minister discovers the existence of a devil-worshiping cult in his seemingly upright Scottish parish. A favorite of CS Lewis, who wrote of it, “for Witch Wood specially I am always grateful; all that devilment sprouting up out of a beginning like Galt’s Annals of the Parish. That's the way to do it.”

Blood Meridian, or: The Evening Redness in the West, by Cormac McCarthy—This was a reread, but it was a special reread for me. This was the first novel by McCarthy that I read as a callow college student more than fifteen years ago, and I was unprepared for it. (I’ve described starting McCarthy’s corpus with Blood Meridian as “jumping into the deep end first.”) But it stuck with me, haunting me, and steadily grew in my regard, and within a year or two I had read almost everything else McCarthy had written up to that point. This year it was finally time to revisit Blood Meridian, and with the intervening years and maturity and experience it was like reading a different novel, or the fulfilment of the novel I struggled with one summer in college—gripping, bleak, and overwhelmingly powerful. So I’m including this reread among my favorite fiction reads of the year, and giving it a stronger recommendation than ever.

Discoveries of the year

Let me here thank my friends Dave Newell and JP Burten (whose novels Red Lory and Liberator y’all should check out) for introducing me to the following two series, of which I read too many volumes to include in the usual “favorites” format above but which I have to acknowledge as highlights of the year:

The Professor Dr von Igelfeld Entertainments, by Alexander McCall Smith—An absolute hoot, these short stories and novellas follow the marvelous philologist Prof Dr Moritz-Maria von Igelfeld, an aristocratic German scholar of the Romance languages and proud author of the seminal 1200-page study Portuguese Irregular Verbs. Von Igelfeld is a brilliant creation, simultaneously pompous and polite, rigid and kindhearted, humorless and eager to please, tone-deaf to social niceties but ostentatiously courtly, jealous of his own honor and childishly naïve. (He does not understand, for instance, why so many other prominent professors have such attractive graduate assistants, or why so many students are so obliging about coed room assignments on what is supposed to be a scholarly reading retreat in the Alps.) This is a charming combination of foibles that consistently lands him in uncomfortable situations ranging from awkward silences to high farce, situations from which he is either too proud or too oblivious to extricate himself. Pure, unalloyed fun.

Volumes read: Portuguese Irregular Verbs, The Finer Points of Sausage Dogs, At the Villa of Reduced Circumstances, Unusual Uses for Olive Oil

Volumes remaining: Your Inner Hedgehog

The Slough House series, by Mick Herron—An excellent series of spy thrillers featuring the outcasts, losers, and screwups of MI5 who, rather than being fired and creating public embarrassment, are shunted into dead-end jobs at a site called Slough House under the management of the slovenly former “joe” or field operative Jackson Lamb. Each volume is intricately plotted, engagingly and suspensefully written, and—what sets it most apart from the novels the series is most often compared to—funny. I’ve enjoyed these so much that I’ve forced myself to space them out so that I can squeeze in other reading.

Volumes read: Slow Horses, Dead Lions, Real Tigers, Spook Street, London Rules, Joe Country

Volumes remaining: Slough House, Bad Actors, and Standing by the Wall

Best of the year:

My favorite fiction read of the year is, for the first time in one of these lists, a reread. I had thought that rereading The Road in 2019 was my favorite that year, but it turns out I had misremembered. The novel is James Dickey’s Deliverance.

Deliverance is notorious in my hometown because John Boorman’s film adaptation was shot there and the movie hangs brooding over us like a specter. Plenty of cultures have to live with unflattering stereotypes, but toothless hillbilly sodomites has to be among the worst. Certainly, the “paddle faster, I hear banjos” bumper stickers got old pretty quick.

But as I discovered when I finally read it during grad school, Deliverance the novel is something else entirely—an involving, horrifying, thrilling, deeply and disturbingly beautiful novel with a rich narrative voice and strong, poetic writing.

If you’re familiar with the movie you already know most of the story; the film adapts the novel quite faithfully. But by the nature of its medium, the film has to deal in visuals, actions, and sounds—externals, surfaces. Dickey’s novel is internal, with deep, swift, very cold currents flowing beneath the surface. Its characters, chief among them narrator Ed Gentry, are all psychologically rich, and the seemingly simple actions of the plot—the drive north, the canoe trip, the horrible encounter with the moonshiners, the flight downriver, ambush, killing, and the final lie meant to flood and hide the events of the canoe trip forever—are complicated and intensified by the characterization and by Ed’s transformation from soft suburbanite to killer, a transformation we witness.

Deliverance is a brilliant novel, an intricately crafted prose poem, a haunting evocation of real environments, a thrilling tale of survival, and a weighty morality play concerning sin, guilt, and the thin layer of civilization far too many trust to keep them from the darkness in their own hearts.

Rereading Deliverance after well over a decade of reflecting on it made this the best fictional read of my year. Though it is not for the faint of heart, I strongly recommend it.

After finishing it this summer, I blogged here about John Gardner’s principle of using vivid, concrete detail to create a “fictive dream” in the mind of the reader and used Deliverance as a major example, comparing it to several other favorites from the spring and summer—Blood Meridian, John Macnab, and Sick Heart River. You can read that post here.

Favorite non-fiction of the year

While fiction threatened to take over my reading this year, I plugged away at a number of good works of history, biography, literary study, and cultural commentary. In the best of these those categories overlapped generously. The following handful of favorites are presented, like the fiction, in no particular order:

In the House of Tom Bombadil, by CR Wiley—An insightful and warmly-written literary, philosophical, and theological look at the meaning and significance one of the most perplexing characters in all of Tolkien’s legendarium. Full review from earlier this year here.

Blood and Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German Empire, by Katja Hoyer—A very good short history of the German Empire (1871-1918) with attention to its origins in post-Napoleonic nationalist movements, political intrigue, and military victory; its politics, finances, and imperial ambitions; its culture and key personalities; and, inevitably, its downfall in the catastrophe of the First World War. Well-structured and balanced and highly readable, this is the best book of its kind that I’ve come across.

The Man of the Crowd: Edgar Allan Poe and the City, by Scott Peeples—An engaging and insightful short study of the life of Edgar Allan Poe and the chaotic, striving, rumbustious landscape of antebellum America through the prism of the cities where Poe lived most of his life. Full review from October here.

Poe: A Life Cut Short, by Peter Ackroyd and Edgar Allan Poe: The Fever Called Living, by Paul Collins—Two elegantly written short biographies of Poe that complement each other nicely. Collins’s biography gives extraordinarily good coverage to Poe’s work for such a concise book, and Ackroyd’s gives greater depth to Poe’s tragic personal life. I’d readily recommend either of these to someone looking for an introduction to Poe that cuts through the manifold myths (insanity, drug abuse, etc etc) and fairly represents the man’s life and work. Short Goodreads reviews here and here.

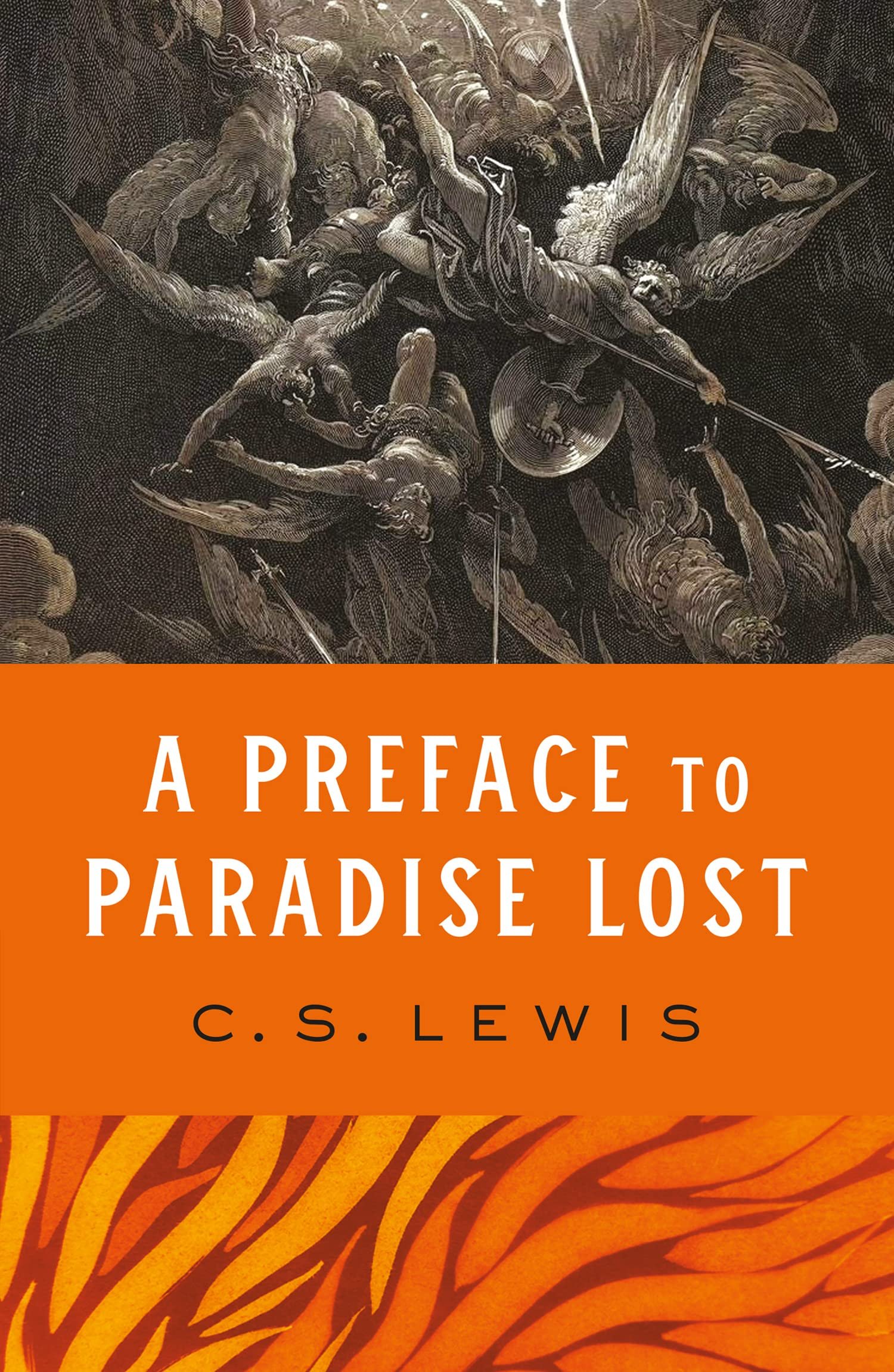

A Preface to Paradise Lost, by CS Lewis—I have tried and failed many times to love Paradise Lost, so I’ll let CS Lewis love it for me. This is an outstanding introduction not only to Milton’s great epic, but to the origins and history of epic poetry generally and to Milton’s place in the story of this genre. Being a fan of epic from Homer to Dante, I most savored the earlier chapters that explain its history and contextualize Milton’s work, but the entire short Preface is an excellent piece of scholarship and worthwhile whether you love Milton or not. (Side note: While I have a very old paperback copy of this book from Oxford UP, I read the nice recent hardback reprint from HarperOne. My only criticism is some slipshod typography, which turned the letters ash (æ) and thorn (þ) in Old English quotations into Œs and Ps.)

The War on the West, by Douglas Murray—A bracing look at the climate of skepticism and outright hostility to Western civilization and the past, with many thoroughly documented examples and a strongly argued case for preserving, maintaining, and celebrating our inheritance. Would pair well with a read of Murray’s longer, more detailed, but more general The Madness of Crowds, one of my favorites of 2020.

Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution, by Carl Trueman—Both a summary and extension of the key themes and arguments of Trueman’s longer and more scholarly The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self—which is high on my to-read list for this year—Strange New World is an excellent guide for general readers to how we got to where we are today, a world in which the transcendent is regarded as an oppressive myth and personal identity and sexuality are market commodities subject to infinitely recursive individual self-revision. A demonstration that ideas have consequences.

Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, by Sean McMeekin—A trenchant reappraisal of World War II with Stalin and the USSR as its central focus. McMeekin reminds the reader that Stalin was as much an aggressor as Hitler—indeed, the two allied to invade and divide Poland, a fact that was memory-holed during the war and has only seldom returned to public consciousness since—and demonstrates that even when Stalin could justifiably claim to be a victim following Nazi betrayal in the summer of 1941, he was a master manipulator who brazenly played the Allies to get what he wanted. And he got everything he wanted. Most damning are the book’s long middle chapters recounting in punishing detail the Lend-Lease bounty continuously heaped upon Stalin, entirely on Stalin’s terms, with Stalin offering almost nothing in return but contempt and ever larger demands, all while dealing high-handedly with Allied leaders and waging war with the same brutality he had brought to the invasions of Poland and Finland. FDR turned a blind eye and forced all around him—from anticommunist members of his administration who found themselves ousted all the way to Churchill himself—to do the same. Stalin’s War both reinforced some conclusions I had already intuited from years of studying and, especially, teaching the war, and placed Stalin at the center of a truly global picture of the conflict and how its results guaranteed decades of Cold War and continued bloodshed. A worthwhile corrective to rosy pictures of World War II—its aims, and prosecution, and its results.

Storm of Steel, by Ernst Jünger, trans. Michael Hofmann—Sharply observed, unflinching, disturbing, and utterly exhilarating, this is one of the greatest war memoirs ever written. Like Blood Meridian, this is a reread of an old favorite that has exercised a profound influence on me, but the rereading experience was so gripping, so bracing, that it deserved to be among my other top non-fiction reads of the year. At the beginning of December I typed up some thoughts, observations, and reflections inspired by this second reading, which you can find here.

Best of the year:

If I cheated a bit by naming a reread as my favorite fiction of the year, I’ll do same here by picking two titles to share a best-of distinction for non-fiction. In this case, both books are fascinating, readable, deeply-researched works of scholarship in Anglo-Saxon history and literature.

The great Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey’s Beowulf and the North Before the Vikings is a short monograph that makes a strong case on a contentious topic.

Less than a century ago, Beowulf was wrongly looked at as a difficult, fatally flawed historical source for the centuries between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of Charlemagne’s Frankish empire, a frustrating farrago of myth and vague allusion to things 19th-century scientific historians wanted straight data about. This viewpoint changed with Tolkien’s 1936 lecture “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” which argued that Beowulf is first and foremost a work of great poetic genius and unsurpassed thematic power, and that the historical elements are there to ground a fantastical story in what, for its original audience, felt like a real world.

Now, Shippey argues, the pendulum has swung too far the other way, with Beowulf viewed only as a poem or myth and neglected as a historical source. Marshaling an impressive array of literary, linguistic, and especially archaeological support from sites like Lejre in Denmark, Shippey argues that Beowulf is not only a great poem but also a broadly accurate and trustworthy window into the region, period, and culture in which it is set—the tribal Germanic peoples of early 6th-century Denmark and Sweden.

Beowulf and the North Before the Vikings is an indispensable read for anyone interested in Beowulf or this time period, and a boon to anyone who, like me, intuited Beowulf’s importance and authenticity as a representation of this world but lacked the archaeological clout to make such a strong case for it.

Just as readable and well-researched but probably of greater general interest is Eleanor Parker’s Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year. In this book Parker, a medievalist who maintained the the excellent Clerk of Oxford blog and has an extraordinary talent for making foreign minds understandable, tackles the nature of time itself—how Anglo-Saxon people thought about and reckoned it, and how they marked and celebrated the passage of it, season by season, year by year.

Parker draws from a huge array of Anglo-Saxon literature—part of the book’s purpose, she writes, is to introduce this literature and encourage people to seek out more of it—to describe first how the heathen Anglo-Saxon peoples’ understanding of time, years, and seasons changed with their conversion to Christianity, and then how they lived their lives within this new understanding. She gives good attention to everything from the number and names of the seasons (originally, it seems, only two: winter and sumor, with spring and fall by many other names imported from the Continent along with Christianity), the months, the work and pastimes of people from all walks of life at different times of year, and, perhaps most importantly, the intricate liturgical calendar and its many, many feasts, rites, and holidays. What emerges through this carefully arranged study is a holistic picture of a lost people and its lost way of life.

Appropriately for a culture whose poetry is so thoroughly tinged with elegy and ubi sunt reflection, I ended this book both delighted and saddened: delighted at the richness of this harmonious yearly cycle and the vividness with which Parker narrated and explained it, and saddened at what has been lost since that time. Winter, and specifically the early days of the twelve days of Christmas, unsurprisingly proved the perfect time to read Parker’s book.

I give my highest and strongest recommendations to both Beowulf and the North Before the Vikings and Winters in the World for anyone interested specifically in the Early Middle Ages and Anglo-Saxon England or for anyone willing to venture out and explore times, places, and minds alien to our own. You’ll find both books richly rewarding.

Rereads

In addition to a lot of good reading this year, I did a lot of good rereading. Rather than pick and choose and then burden y’all with more one-paragraph summaries, I’ve simply listed all of them as usual. But by virtue of my having taken the time to revisit these this year, please understand all of them to rank somewhere between good and excellent. Audiobook “reads” are marked with an asterisk.

Devil May Care, by Sebastian Faulks*

Russell Kirk’s Concise Guide to Conservatism*

After Nationalism: Being American in an Age of Division, by Samuel Goldman

Blood Meridian, or: The Evening Redness in the West, by Cormac McCarthy

Socrates: A Man for Our Times, by Paul Johnson*

The Hobbit, by JRR Tolkien

The Forever War, by Joe Haldeman*

The Thirty-Nine Steps, by John Buchan

Greenmantle, by John Buchan

How to Stop a Conspiracy: An Ancient Guide to Saving a Republic, by Sallust, trans. Josiah Osgood

Deliverance, by James Dickey

Gisli Sursson’s Saga and the Saga of the People of Eyri, trans. Martin Regal and Judy Quinn

Das Nibelungenlied, trans. Burton Raffel

Beowulf, Dragon Slayer, by Rosemary Sutcliff

Life of King Alfred, by Asser, trans. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge

Storm of Steel, by Ernst Jünger, trans. Michael Hofmann

The Third Man, by Graham Greene

Kids’ books

All of the books listed below were read-aloud favorites for myself and our kids this year. I had a hard time narrowing this selection down, but these are certainly the favorites, and I’d recommend any of them without hesitation.

Caedmon’s Song, by Ruth Ashby, illustrated by Bill Slavin. A beautifully illustrated children’s version of an important Anglo-Saxon story related by Bede. Short Goodreads review here.

Myths of the Norsemen, by Roger Lancelyn Green—An old favorite of mine that proved an excellent introduction to these stories for my seven- and five-year old.

Alexander the Great and The Fury of the Vikings, by Dominic Sandbrook—Two volumes from Sandbrook’s Adventures in Time series that I read out loud to my kids this fall and winter. Perfect for our seven-year old, who thrilled to Alexander’s campaigns and the various Viking Age figures (e.g. Ragnar Loðbrok, Alfred the Great, Leif Eiriksson, and Harald Hardrada), and though our five-year had a somewhat harder time tracking with the stories he still enjoyed them. I strongly recommend both and look forward to other entries in the series.

Basil of Baker Street, by Eve Titus—A fun, light, nimbly paced adventure with a clever mouse-level perspective on Sherlock Holmes and just enough of the trappings of Conan Doyle’s stories to hook new fans.

Read-n-Grow Picture Bible, by Libby Weed, illustrated by Jim Padgett—A childhood favorite, a surprisingly thorough and serious illustrated Bible, read to my kids over several months. Short Goodreads review here.

A Boy Called Dickens, by Deborah Hopkinson, illustrated by John Hendrix—A delightful and beautifully illustrated short retelling of Charles Dickens’s childhood and the influence growing up among the workhouses and debtors’ prisons of industrial London had on his imagination.

The Best Christmas Pageant Ever, by Barbara Robinson*—A hilarious and genuinely moving Christmas tale that combines farce, nostalgia, and remarkable depth, especially on one of my favorite themes: the foolish things of the world confounding the wise. My whole family enjoyed this greatly on our car trip to Georgia for Christmas.

Conclusion

If you’ve read this far, thank you for sticking with me, and I hope you’ve found something enticing to seek out and read during the new year. Thanks for reading, and all the best in 2023!